Usage Creep Featured Pattern: P1285 December 2018

Abstracts in this Pattern:

Companies are finding more ways to leverage users' personal information to improve existing services and develop new ones; however, companies sometimes engage in usage creep—gathering and leveraging this information in ways that go beyond what users expect or intended to permit. For example, reports suggest that third-party developers regularly access the email inboxes of users of Google's (Alphabet; Mountain View, California) Gmail and develop software products and services on the basis of individuals' data. Although Google announced in mid-2017 that it would stop scanning Gmail inboxes, the company still allows third parties to access Gmail for development purposes.

Examples of usage creep also appear in the consumer-genetics industry, where companies may use customer-provided genetic information in ways customers did not expect or agree to. People submit their DNA to companies such as Ancestry.com (Lehi, Utah) and 23andMe (Mountain View, California) to obtain health or genealogical information, and these companies establish large DNA databases. Parabon NanoLabs (Reston, Virginia) has used such databases to solve years-old cold cases by comparing DNA evidence from a crime scene with DNA samples in the databases. Many people who submit their DNA to consumer-genetics companies were unaware that their genetic information would see use in law-enforcement applications. And GlaxoSmithKline (GSK; London, England) and 23andMe recently announced a partnership that gives GSK access to 23andMe's genome database for use in researching diseases and developing new cures. This application goes beyond what many customers agreed to when they provided their genetic information. Though customers can opt out of their genetic information's seeing use in research, customers who consent may be unaware of the specifics of how companies use their data.

Concerns about overstepping in the collection of data also exist. A group of Naperville, Illinois, citizens recently brought a case against the City of Naperville, arguing that new smart electricity meters performed unreasonable search by recording electricity consumption in homes every 15 minutes. The court ruled that although the actions did constitute search, the search was not unreasonable in the context of measuring power consumption. Likely, follow-up cases will have to define with greater clarity when search exists and when it is unreasonable.

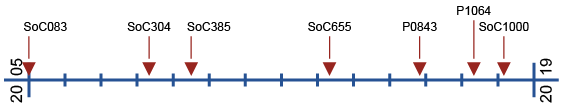

The Development of this Pattern

Data Points

- SC-2018-10-26-008

Reports suggest that third-party developers regularly access the email inboxes of users of Google's Gmail and develop software products and services on the basis of individuals' data. - SC-2018-10-26-083

Parabon NanoLabs has used DNA databases to solve years-old cold cases by comparing DNA evidence from a crime scene with DNA samples in the databases. - SC-2018-10-26-069

A group of Naperville, Illinois, citizens recently brought a case against the City of Naperville, arguing that new smart electricity meters performed unreasonable search by recording electricity consumption in homes every 15 minutes.

Implications

P1285 — Usage Creep

As data become increasingly easy to gather and use, companies sometimes do more with those data than users bargained for.

Previous Alerts

- SoC083 — Proliferating Privacy Threats (January 2005)

Although public awareness of privacy problems seems to grow at a linear rate, potential threats to privacy seem to be emerging at an exponential rate. - SoC304 — Privacy-Infringing Business Models (May 2008)

Are business models that depend heavily on access to personal data first steps to customized, on-demand services? Or are they the first dangerous missteps down the long slippery slope of privacy abuse? - SoC385 — Evolving Privacy Expectations (July 2009)

People's reasonable expectation of privacy is evolving. Enhanced data capture and monitoring technologies also add to existing privacy concerns. - SoC655 — Big Data, Big Concerns (May 2013)

Although big-data applications undoubtedly offer many benefits, organizations must watch out for potential pitfalls such as spurious analysis, lack of ethical frameworks, and privacy infringements. - P0843 — Privacy and Security: A Delicate Balance (November 2015)

New technologies are enabling an increasing level of government surveillance and control. What is the right balance between security and privacy? - P1064 — Data and Privacy, Safety, and Security (May 2017)

The increasing collection and analysis of personal data are creating a complex interplay among privacy, safety, and security. - SoC1000 — Losing the Fight for (or Interest in) Privacy (March 2018)

People often express the opinion that defending privacy is crucial, yet they rarely take actions that defend privacy as a crucial value.