The Future of Forecasting Featured Pattern: P0779 May 2015

Abstracts in this Pattern:

Two notable efforts investigate new forecasting approaches: the US Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA; Washington, DC) Aggregative Contingent Estimation (ACE) Program and the Value at Political Risk (Vapor) model, which is the result of a collaboration between risk adviser and insurance broker Willis Group Holdings (London, England) and consultancy Oxford Analytica (Oxford, England).

IARPA's ACE Program has sought to improve forecasting of geopolitical events by exploiting recent research from the social sciences, insights from behavioral economics, and experience with prediction markets. Five teams from universities and research centers around the United States built forecasting systems, enlisted experts, and competed to provide the most accurate forecasts about events the IARPA identified as of particular interest. The winning team from the University of Pennsylvania (Penn; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) succeeded in part because it developed a training program for team members that included education about the biases and flaws in reasoning that normally trip up forecasters, it gave team members constant feedback about the accuracy of their previous forecasts, and it allowed team members to work in collaborative groups. The Penn team was also able to identify several attributes that make for better forecasting, including open-mindedness, general cognitive ability, and patience in assessing data.

The Vapor political-risk model pushes risk analysis and forecasting in a completely different direction. Vapor is a large simulation that aims to identify major variables in global and national events and the character of their interactions, to assign probabilities to those events, and to estimate the financial cost of various scenarios. In effect, Vapor adapts some of the tools developed by the reinsurance industry—which are concerned with quantifying the effects of phenomena such as climate change and terrorist attacks—to political-risk analysis.

Although these two efforts go in very different directions, they both explore basic questions about forecasting and challenge basic assumptions in futures. These efforts suggest that although predicting the long-term future may be impossible, accurately forecasting near-term events may be more feasible than practitioners thought it was.

The Development of this Pattern

Data Points

- SC-2015-04-01-068

The US Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity's Aggregative Contingent Estimation (ACE) Program has sought to improve forecasting of geopolitical events. - SC-2015-04-01-036

ACE's winning team from the University of Pennsylvania succeeded in part because it identified several attributes that make for better forecasting. - SC-2015-04-01-091

The Vapor political-risk model adapts tools developed by the reinsurance industry to political-risk analysis.

Implications

The Future of Forecasting

Recent efforts show the very different ways that researchers are trying to develop foresight methods for the twenty-first century.

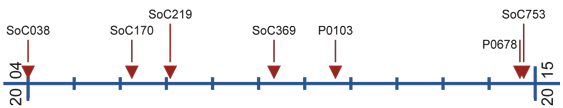

Previous Alerts

- SoC038 — Bettor Predictions (January 2004)

Domain experts willing to bet (their own money) on the outcome of future events turn out to be fairly accurate predictors when a large enough number of experts participate in the betting. - SoC170 — Predictions and Behavior (April 2006)

Making predictions is tricky. The combination of predictions and human behavior is a particularly volatile mixture. Although helpful in many instances, the use of predictive models raises a number of questions. - SoC219 — Forecasting on Fast-Forward (February 2007)

Researchers are finding ways to improve forecasting techniques by collecting and analyzing vast amounts of data, by developing distinctive tools for particular types of forecasting, and by identifying which factors to exclude from analysis because of their inherent uncertainty. - SoC369 — Prediction Is the Future (May 2009)

Technologies now exist that can anticipate a variety of phenomena, from crime to illness. For a whole host of industries—from security to marketing to health care—prediction is the future. - P0103 — New Predictive Tools (September 2010)

A new round of prediction technologies will spur the growth of innovative predictive—and controversial—applications. - P0678 — Mining the Future (September 2014)

New data-mining methods promise to reveal information about developing events and technological advances, perhaps offering a glimpse into the future. - SoC753 — The Art or Science of Forecasting (October 2014)

Precise but inaccurate forecasts result in incorrect conclusions that lead to misguided strategies.